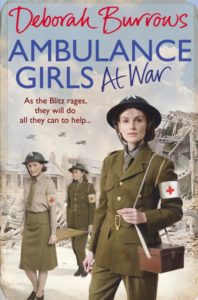

I have a soft spot for a good mystery. My first three books A Stranger in my Street, Taking a Chance and A Time of Secrets were all ‘whodunnits’ set in WW2.

Which is why I was delighted to attend the inaugural Capital Crime Writing Festival in London last week.

The first session I went to was “The Influence of Agatha Christie”. Like many authors, I remember reading an Agatha Christie as my first ‘grown-up’ book.

Listening to the panel reminded me of a time in WWII when the Queen of Crime was suspected of using one of her books to send coded messages to the Nazis.

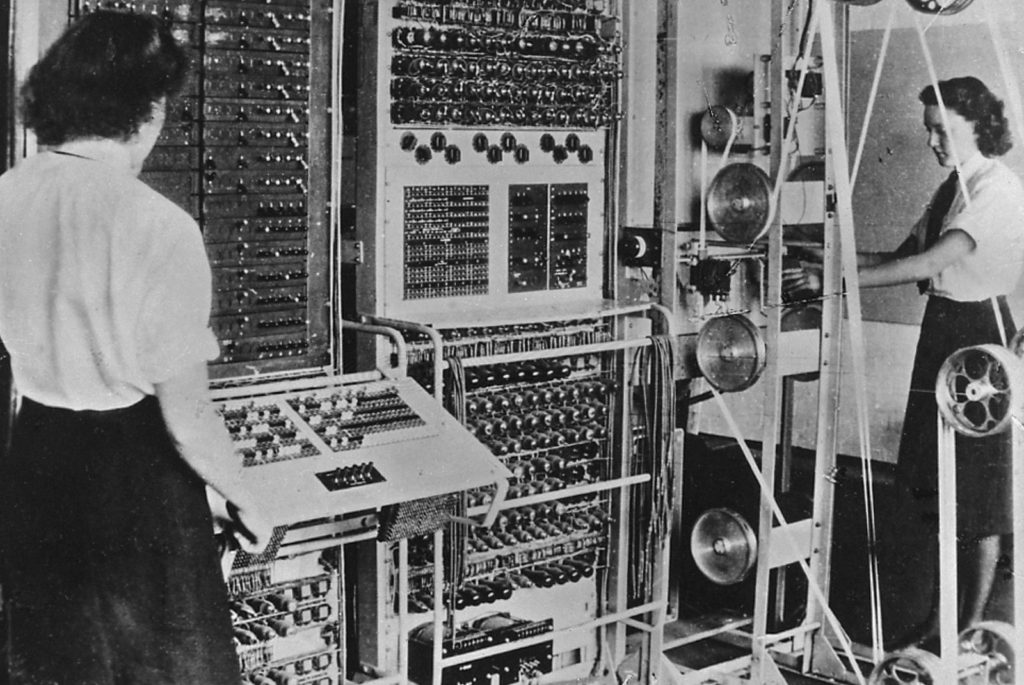

It relates to the codebreakers at Bletchley Park near Milton Keynes, which is one of my favourite museums.

During WWII a small group of code breakers at Bletchley Park developed techniques for decrypting messages coded using electrical cipher machines that the Germans considered ‘unbreakable’. The flood of high-grade military intelligence deciphered by Bletchley Park was code-named Ultra.

The messages included information about German spies in the UK, which led to the capture of every German spy in the country. Most became double agents under the British Double-Cross Operation and were used to disseminate false intelligence to the Abwehr (German Military Intelligence).

It is estimated that the codebreakers at Bletchley Park shortened the war in the Atlantic, the Mediterranean and Europe by between 2 and 4 years and may even have altered its outcome.

It was crucial that the enemy remained wholly unaware of the work being done at Bletchley Park.

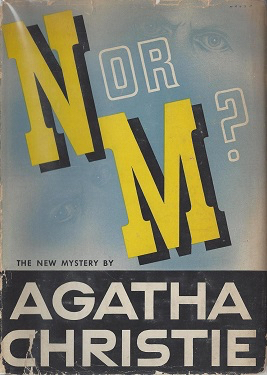

At the same time that the Bletchley Park codebreakers rushed to break the German Enigma code, Agatha Christie was writing her first spy thriller.

In N or M, which was published in 1941, the daring detective pair, Tommy and Tuppence Beresford, are recruited by British Military Intelligence to discover the identity of a German spy. An important character in the book is Major Bletchley, an annoying retired Indian army major, who professes to have inside knowledge of the war.

Like all Christie’s books it was a best-seller, but it caused consternation in MI5. Was Christie sending a message in the novel, letting the enemy know that not just the fictional Tommy and Tuppence, but also MI5 were unmasking German agents? Was she divulging that “Bletchley” was significant in this?

Or was it all just a strange coincidence?

Agatha Christie was ‘the Queen of Crime’. If MI5 agents or the police went to interrogate Christie about her choice of character name, it might bring damaging publicity.

MI5’s Chief Cryptographer at Bletchley Park was Alfred Dillwyn “Dilly” Knox, who was a close friend of Agatha Christie. MI5 had a word with him about it. Although he considered it laughable that Christie knew anything at all about what was going on at Bletchley Park, he agreed to talk to her.

He did so in a very British manner. Over tea and scones at his home in Buckinghamshire, Knox asked Christie in a light-hearted manner how she arrived at the names of the characters in her books. Major Bletchley, for instance, in her latest novel.

Christie gave an innocent explanation. She had been stuck at Bletchley Railway Station, on her way by train from Oxford to London. Annoyed at the long delay, she took revenge by giving the name Bletchley to one of her least loveable characters.

Knox reported back to MI5, who were apparently reassured by this explanation.

And yet…

In the 1940s the route of the (now defunct) “Varsity Line” between Oxford and Cambridge went through Bletchley. But Christie said she was on her way to London. Why would she go to Bletchley when there was a direct Oxford-London line she could have taken?

She may have had no choice. German bombings meant the UK railway service was in a parlous state at that time. Diversions and long delays for non-military transport were common and very irksome to travellers. Christie’s explanation for using “Bletchley” may be the simple truth.

But there is another, very interesting facet to the story. During the Second World War, and when she was writing N or M, Christie lived at the Isokon building in Hampstead, an avant-garde 1930s apartment building.

I have visited the Isokon, in which reinforced concrete was used in British domestic architecture for the first time. It was designed for well-heeled tenants who wanted a minimalist lifestyle with few possessions and who didn’t like cooking. The apartments had no kitchen, but food could be ordered from a general kitchen on the ground floor.

The tenants it attracted included around twenty-five Soviet Russian spies, who lived there between the mid-1930s and mid-1940s.

In fact, one of Christie’s neighbours was Arnold Deutsch, the controller of the infamous spy group of Kim Philby, Guy Burgess, Donald McLean and Anthony Blunt.

The Isokon is not a large building and Christie must have known her neighbours. Was it co-incidence that while living there, she first tried her hand at a spy novel? Or did Christie overhear something in the Isokon that provided the seed for her spy story?

Was it coincidence that she should give a character in that novel the name of the top-secret establishment where British codebreakers led by her close friend were deciphering Nazi messages, including those relating to German spies in Britain? Had Dilly Knox himself innocently mentioned Bletchley Park in Christie’s hearing? Or was the railway station story the truth. Or was it a mixture of the two?

J.R.R Tolkien is quoted as saying that a story:

grows like a seed in the dark out of the leaf-mould of mind: out of all that has been seen or thought or read, that has long ago been forgotten, descending into the deeps.

J.R.R. Tolkien

I’m sure Christie herself had no idea how, but the name “Bletchley” allied to the idea of German spies slipped into the leaf-mould of Agatha Christie’s mind and took root there.

![By Miguelacbt1987 [Public domain], from Wikimedia Commons](https://deborahburrows.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/800px-Wadham_4-300x225.jpg)