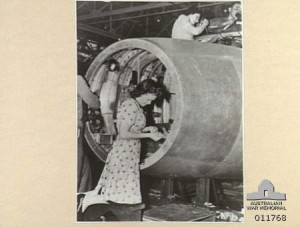

“The first thing you noticed when you met an American, was their manner. They had very good manners with women. A woman likes to be spoken to properly, and naturally when they were treated so well by the Americans, the reaction was quite profound. Almost everyone went out with some Americans, because they were just everywhere and we had no Australians to dance with.” Joy Boucher, aircraft construction worker, Sydney.

The first Americans arrived in Brisbane on 22 December 1941. By mid 1943 there were were 150,000 in Australia, with the largest concentrations in Queensland (near Brisbane, Rockhampton, and Townsville). But US naval forces were also frequently anchored at Sydney and Perth. General Douglas MacArthur, who was appointed as the Supreme Commander of South-West Pacific Area on 18 April 1942, was based in Melbourne before he moved to Brisbane.

Almost one million American service personnel passed through Australia during World War 2. Cafés began advertising Coca-Cola, coffee, and hamburgers. Hot-dog stands appeared. By the end of 1944, two-thirds of Australia’s imports came from the United States.

The Diggers were a poor bet when it came to showing a girl a good time, because the Yanks did earn a lot more money. American soldiers in the lower ranks earned twice the amount of their Australian counterparts – a US private earned the same as an Australian captain. In the higher ranks the disparity was even more pronounced. These differences in pay scales, their stylish uniforms (with zippered flies!), and their custom of tipping earned the Americans a reputation as “big spenders”.

“There were so many things that are different from now and men had buttoned flies, all army uniforms had buttoned flies, and then along came the Yanks and they had zippers – and you found yourself trying not to look. They really made the front ofmthe trousers very neat, I tell you and they didn’t really come into the civilian population in Australia, zippers, until the war had ended – but oh, very neat.” Patsy Adam-Smith, VAD nurse.

Many Australian women saw the well-paid Americans as desirable and romantic. More than 12,000 Australian women became American war brides, most of whom returned to the US with their new husbands at the end of the war.

Not all ended happily. This is a studio portrait of Dorothy Irene Nuttah-Singh of Sydney with an unknown American sailor to whom she was engaged. Nuttah-Singh fell in love and got engaged to the US sailor after a brief courtship in Sydney during the war. He promised to take her back to the United States to marry when he got leave from duty. After serving in the war zones, he returned to Sydney with his ship, which was then heading home via Guadalcanal to an extended leave. He told her that as soon as he got home he would return for her, but his ship was sunk en route with all lost. She learned of his death by listening to the radio. She remembers all her female friends were crowded around the radio and after several ships were named, his ship was named and that was all. His family knew nothing of her. She was left with an engagement ring and this photograph.

Sometimes